Artist biography

Hawkinson’s studio practice is also her advocacy practice. As an artist, advocate and chaplain living in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, her work is about crossing borders that are ideological, psychological and physical. She works in textiles, installation art, video, soundscape and public interventions. As a newcomer on the unceded and traditional territories of the Musqueam, the Squamish and the Tsleil-Waututh peoples, she is aware of the implications of contested territories and inaccurate histories. This led to research trips in the contested territories of Israel/Palestine and Northern Ireland to attempt an understanding of the mechanisms behind societal division, sectarianism and othering.

Her research trips to these places resulted in several visual art exhibitions. In 2018 she exhibited Origin Stories in Edmonton, Alberta. The show was loosely autobiographical and went into personal mythologies and story-telling. In 2019 she was invited to the Czech Republic to speak on the intersections of art, faith and community development. In 2019 she exhibited a body of work created from several trips to Belfast. Pushing Through a Brick Wall is a soft manifesto. Through absurd artistic interventions the words seek to subvert divisive structures, both physical and idealogical. For instance, Interface is a video that documents the journey of a plastic bag blown along, through and over Peace Walls in West Belfast. The show explores conflict through engagement with textiles to create a “soft space” for dialogue.

Similar to her art, Hawkinson’s roles also cross boundaries. Art becomes advocacy, advocacy flows into spiritual care, and spiritual care leads back to art actions. Locally she collaborates with a guerrilla theatre group to challenge the stigma of illicit drug use, catalyzing social change through art and advocacy. She has lead community murals and participates in creative intersectional community building. Even her community house is a site for unlikely friendships to form. Kinship and conviviality are at the root of her practices.

In the past year, her research hit closer to home. Keenly aware of her inability to reconcile the cognitive dissonance around family and politics, she dove into a study of conflict engagement through field recording and soundscapes. The research culminated in the public intervention; Call & Response. The piece was an original score transcribed from a protest and performed by a brass band beneath a bridge. It explored themes of dissonance and negotiation through musical improvisation.

Project Questions:

What are the missing interfaces between noise and sound? Protest and dialogue? Public and private space? The collective/communal and the individual?

How can a flashpoint be transformed into a generative, convivial space?

How can a collective use of “city as stage” affect social change that transcends demographic boundaries and catalyzes communities towards kinship?

___________________________

“Lacking a sense of microcosmic community, we fail to protect our macrocosmic global home. Can an interactive, process-based art bring people ‘closer to home’ in a society characterized by what George Lukács called ‘transcendental homelessness’?”

With Sounding the City I hope to create a collaborative artist residency/occupancy in a public square of my city. It’s about building a creative ecosystem where participants, through invitation or sporadic encounter, are invited to experiment with listening to and “sounding” the urban environment—an action to inspire deeper connection with place and people.

My artistic practice is research and place-based. It is deeply connected to the work that I do in my community. As a conceptual artist, advocate and outreach worker living in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, my art practice and work are about crossing ideological, demographic and physical borders. I work with textiles and installation art, video, soundscape and public interventions. The narratives of displacement in Vancouver’s history, specifically in my neighbourhood, have fuelled cultures of activism and creative resistance which inform my practice. I resonate with the ethos and aesthetics of the Fluxus Arts Movement and punk d.i.y. subculture. Improvisation, provisionality, resource sharing and artistic models for community care are the foundation of my creative practice. It is from this foundation, with years of experience in communal living, that my creative research will extend to engage with the public.

I am interested in synthesizing conflict engagement practices with aesthetics, and have pursued education and mentorship in this area to inform my arts practice. I’ve visited regions with conflict narratives to research the mechanisms behind sectarianism and othering. While in Bethlehem, Palestine, I made work to engage with themes of repatriation. I experienced the tension, violence and myth surrounding the separation barrier between Israel and the West Bank. In Belfast I stayed in a unionist enclave surrounded by a larger republican community, hoping to gain an understanding of the deep sectarian rifts. Neighbourhoods in West Belfast are divided by walls to protect people. Ironically the “peace walls” (also called interfaces) perpetuate division; at times becoming flashpoints for violent conflict. During a residency I filmed a performance where I made a charcoal rubbing of bricks on a tablecloth, later washing the brick imprints out in a stream. Pushing Through a Brick Wall is about transforming a rigid structure to something soft and malleable. It’s about creating a third space where the awkward work of mediation can take place. I seek to understand how flashpoints can be subverted into convivial sites where power imbalances are confronted and authentic dialogue with “the other” is possible.

Vancouver’s contested territories don’t hold the same weight as sites with active conflict, but the tensions exist, simmering beneath the surface. Beyond the utilitarian use of the public square for monuments, I see it as a site of spillage from private to public life, a site where boundaries are blurred. In theory accessible to all, public space is far from neutral. Paula Jardine, a community-engaged artist, speaks to the redefining of public space as human space: “By taking over and transforming public space, we reclaim human space and bind community, building connections and empowering people to address other issues that affect the life of the community.” Public space is political. Politics is theatre. The city is a stage. In Artificial Hells, Claire Bishop quotes Kerzhentseve, “Why confine theatre to the proscenium arch when it can have the freedom of the public square?’” She goes on to write, “Monumental outdoor spectacles encouraged mass participation, sublating individualism into visually overpowering displays of collective presence.”

Public squares are human spaces. They host a diversity of individuals, other beings, ideologies and activities. Dorit Cypis, the founder of Peoples Lab, maps out a formula, writing, “Identity and difference equals conflict, which equals opportunity.” She offers a hopeful way of engaging with tensions stemming from difference. Donna Haraway writes, “Making kin seems to me the thing that we most need to be doing in a world that rips us apart from each other, in a world that has already more than seven and a half billion human beings with very unequal and unjust patterns of suffering and well-being.”

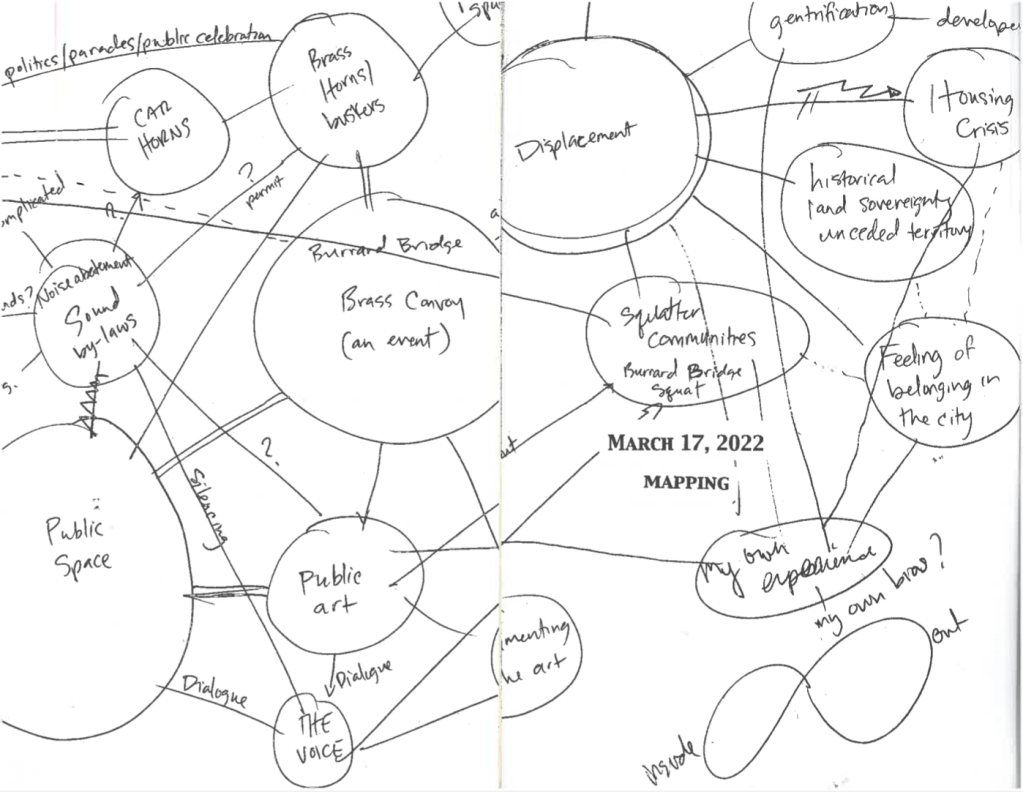

Last year I performed an intervention in Vancouver. Call & Response explored dissonance and negotiation through musical improvisation. Keenly aware of my inability to reconcile my cognitive dissonance with family and right wing politics, I began a research project synthesizing conflict engagement practices with sound studies. The research culminated in a 16-piece brass score transposed from my field recording of horns from the “freedom convoy” that rolled through Canada last spring. The score was performed beneath a bridge with musicians I met while wandering through the city. We performed the score in six variations, with each one creating an experience of dissonance, resonance and harmonies. Through my research I came across the phrase “working with the sound.” This became foundational for Call & Response. Social practice artists Suzanne Lacy and Estella Conwill Major write, “Blues musicians know how to work with the sound. They explore possibilities of new rhythms and variations from within and breaking out of the structure. Working the sounds means that I am involved in something that engages me, that confronts my prejudices, fears and limitations. From here, we can explore variations and new realities.” Accompanying the performance is a zine that compiles the score with my research and reflections. The reader is invited to wrestle with their own dissonance, creating improvisations towards new realities.

Working with the sound raised questions about the missing interfaces between noise and sound, public and private space, protest and dialogue, and the communal and the individual. It made me realize that soundand public space are intricately connected. Judith Butler discusses bodies in public space in her seminal work, “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street.” She investigates how a crowd both affects and is affected by its environment, writing “…When we think about what it means to assemble in a crowd, a growing crowd, and what it means to move through public space in a way that contests the distinction between public and private, we see some way that bodies in their plurality lay claim to the public, find and produce the public through seizing and reconfiguring the matter of material environments; at the same time, those material environments are part of the action, and they themselves act when they become the support for action.” To Butler’s comments I would add voices in plurality. How does communal sound change the way we inhabit space? Could this be a way of sounding the city?

Can a collective use of the city as a stage catalyze relationships and social change that transcend demographic borders? What would it look like to see the community as a living, breathing monument? I hope to create durational public site-specific artworks that are provisional and community oriented; to stir subversive conviviality as a response to the immovable monuments and ideologies that separate us. Sounding the City will be an experiment in building a creative, participatory ecosystem within the public square where we explore new ways of being together through collaborations with local and international artists, activists and residents, together sowing into the collective memory of the city.

Methodologies

Gathering : Someone once said of me that I “collect people.” I am committed to the gathering of people into unlikely and authentic communities. I’ve been rooted in local artist and activist communities in Vancouver for more than a decade. My passion for building community has served in my personal life with intentional community housing, as well as bringing people together for playful/political interventions. My philosophy behind gathering is that there will always be enough if we are generous with our resources. I gather to redistribute; whether that be friendships, knowledge, material resources, housing, or platforms. This research project will rely on the community organizing practices that I’ve learned over the years. It will also require gathering information through reading first person sources and articles, books on collective arts practice and conflict engagement.

Site Specificity: I prefer to create work about a place while I’m in that place. My studio is full of materials found and repurposed to speak to issues of displacement, homecoming and nationalism. I will spend time in the Vancouver City Archives searching for lesser known narratives, seeking out people with lived experience and creating artwork that is deeply informed by the place it is situated.

Field Recording : My work is informed by R. Murray Schafer’s life work in soundscape studies. I collect field recordings in urban environments, mixing the sounds to gain a deeper understanding of the collective voice, both human and non-human. This also allows me to listen intently to my surroundings. Sound studies are an accessible way to invite others to connect with their environment.

Mediation Practices: An interest in contested territories led me to visit and learn from communities who are committed to non-violence in oppressed regions. In recent years I’ve audited courses on peace building and reconciliation, taken workshops on mediation and aesthetics and been mentored by professionals in the field. I hope to bring in somatic and creative practices that circumvent dogmatic and binary thinking, in my own work and in collaboration with others.

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah, et al. The Human Condition. The University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Bennett, Jill. Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford, CA. Stanford University Press, 2005.

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso, 2022.

Burton, Johanna, et al., editors. Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good. Cambridge, MIT Press, 2016.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University press, 2016.

Kelly, Caleb. Sound: Documents of Contemporary Art. Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press, 2011.

Kuoni, Carin and Chelsea Haines. Entry Points, the Vera List Centre Field Guide on Art and Social Justice No. 1. Durham, NC, Vera List Centre, 2015.

Kwon, Miwon. One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. 1st ed., Cambridge, MIT Press, 2002.

Lacy, Suzanne. Leaving Art: Writings on Performance, Politics and Publics, 1974-2007. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 2010.

Lacy, Suzanne (ed). Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle, Bay Press, 1995.

Lederach, John Paul. The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace. Reprint, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Lederach, John Paul. Building Peace; Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington, DC, United States Institute of Peace Press, 1997.

McLagan, Meg and Yates Mckee, editors. Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism. New York, Zone Books, 2012.

Molleson, Kate. Sound within Sound. Faber & Faber, 2023.

Nelson, Maggie. On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint. Graywolf Press, 2022.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Tuning of the World. Toronto, McClelland and Stewart, 1977.

Stiles, Kristine, and Peter Howard Selz. Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings. University of California Press, 2012.

Willard, Tania. Access All Areas: Conversations on Engaged Art, Visible Arts Society, Vancouver, BC, 2008, p. 23.

Artist Bio

jennyhawkinson.com